Revealed: How British engines ended up in Israeli drones

Earlier this year, an Israeli state-owned arms company released an advertisement for its newest generation of military drones.

The advert showed two men driving a van through dense woodland before getting out to unload the cargo: an Apus 25 drone, manufactured by Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI) and Aerotor.

According to IAI, the Apus 25 is a “revolutionary long-endurance TactiQuad” which will “redefine tactical drone operations for ground and maritime forces worldwide”.

The drone’s versatility extends to “offensive operations”, meaning it can “effectively deploy… weapons systems, adding a new dimension to tactical air support in combat scenarios”.

IAI’s advert not only flaunted the capabilities of the new drone but also inadvertently exposed a logo on the engine which showed it was made by RCV Engines, a British engineering firm based in Dorset.

Weeks after Declassified revealed how British engines were in the Apus 25, RCV Engines announced it had “given notice of termination of support to our Israeli customer”, understood to be Aerotor.

But this was only half of the story.

RCV Engines had boasted about managing to “remove the need for an export licence when shipping worldwide” in 2022, suggesting the engines were shipped to Israel as unclassified goods.

How could this be possible?

Declassified has now obtained documents via the Freedom of Information (FOI) Act which suggest several UK companies have been shipping drone engines without the need for any export licence.

They have apparently been doing this by saying their engines are not “specially designed or modified” for military use, even when they are being exported for use by an arms firm.

The revelation points to a glaring loophole in Britain’s arms export regime which indicates drone engines could have been shipped to Israel without any governmental oversight amid the genocide in Gaza.

Emily Apple from Campaign Against Arms Trade told Declassified: “Successive governments have lied to us. They have claimed that the UK has one of the most robust arms export control systems in the world.

“Nothing could be further from the truth. These documents suggest that government departments have wilfully colluded with a private company to allow them to export military equipment with no accountability.

“There are also urgent questions that this government needs to answer about how widespread this practice is and what other companies are using this outrageous loophole”.

‘Remove this classification’

The UK government has a list of strategic military and dual-use items which require export licences.

In section ML10, aircraft, drones, and aero-engines “specially designed or modified for military use” are listed as items requiring such licences.

Documents obtained by Declassified through an FOI request suggest the wording of this section has allowed British engine manufacturers to supply arms firms if they can argue their engines were not specially designed or modified for military use.

For instance, if an engine was initially designed for civil purposes but can also be attached to a military drone, the manufacturers can seemingly make a case for removing that engine from export controls.

The documents obtained from the Department for Business and Trade detail how RCV Engines contacted the department in September 2021 about “the problem in hand i.e. the licence to Israel”.

By late 2021, RCV Engines had become convinced that none of its engines required export licences and that previous applications had “been made in error”.

This, one RCV Engines employee wrote, had been “confirmed” during their “recent attendance” at a “training session” organised by the trade department about arms export licences.

On 8 November 2021, RCV Engines wrote again to the trade department to enquire about its licensing situation.

The response came two weeks later, with the trade department seemingly pointing to the loophole in the arms licensing criteria.

An official wrote: “We would like to understand… the engine’s evolutionary journey to determine whether the original design intent of the engine, or its predecessors, was military or not, or whether military modifications have been made”.

Another email dated 6 December 2021 with subject line “specifically designed or modified for military use” has been redacted in its entirety.

‘The ideal outcome’

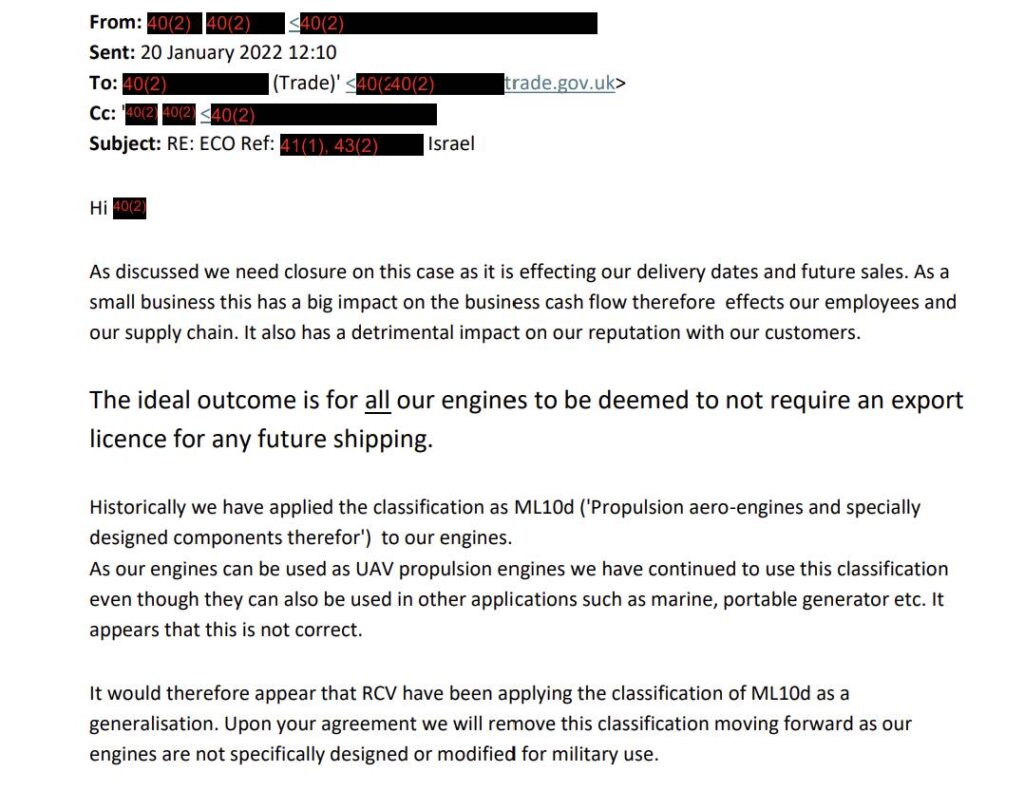

By January 2022, an RCV Engines director was telling the trade department that the company’s engines should fall outside the export licence regime entirely.

“The ideal outcome is for all our engines to be deemed to not require an export licence for any future shipping,” they wrote.

Historically, the director said, the company had applied for export licences under the ML10d classification, covering propulsion aero-engines and specially designed components.

Portion of FOI request obtained by Declassified

The next paragraph was redacted by the trade department, but in another copy of the same email released to Declassified, the information is visible.

In that paragraph, the company official wrote: “As our engines can be used as UAV propulsion engines we have continued to use this classification even though they can also be used in other applications such as marine, portable generator etc”.

They argued that “it would therefore appear that RCV have been applying the classification of ML10d as a generalisation. Upon your agreement we will remove this classification moving forward as our engines are not specifically designed or modified for military use”.

The email concludes: “Ultimately we supply engines and not weapons”.

The correspondence strongly suggests RCV Engines was aware its engines could be used for military purposes but sought to exploit the loophole offered by the wording in ML10 to export them without a licence.

An RCV spokesperson told Declassified: “RCV Engines makes small capacity internal combustion engines for use in a variety of applications some of which are Unmanned Aerial Systems. There is no aspect of the RCV Engine design that is ‘specifically designed or modified for military use’.

“Other uses of our engines have included forest & garden tools, hobbyists’ aircraft, generators and commercial drones.

“Amongst many customers, RCV Engines supplied 19 prototype engines to an Israeli UAV developer which was looking to develop some new drones for wildfire detection in the USA and Western Europe”.

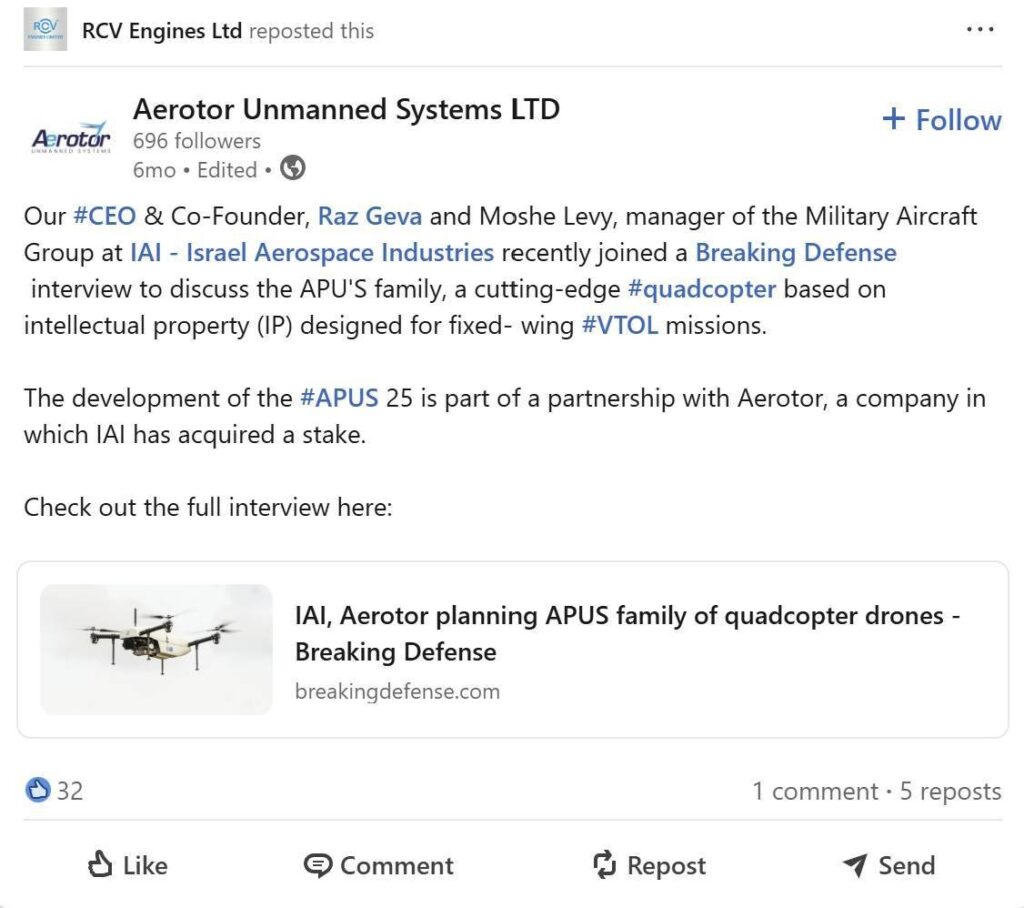

However, RCV Engines shared a post from Aerotor on LinkedIn in 2024 about the military applications of the Apus 25 drone, powered by its own engines.

The company’s spokesperson further confirmed that shipments to Israel continued amid the Gaza genocide, saying: “Shipments to this Israeli customer commenced in 2021 and ended in February 2025. We have terminated all trading relationships with Israel.

“Our Engines fully comply with export regulations, and this has been confirmed by the UK Government. The engines were classified for export purposes as ‘commercial use’ in compliance with ML10d, from which they are exempt.

“With this classification, we are competing on an equal playing field with competitors producing many similar size engines with multiple applications, whose identities are in the public domain.”

Helping hands

Around the same time its employees were making their case directly to the trade department, RCV Engines was assisted in its effort to resolve its licence “problem” by the local MP in Christchurch, Christopher Chope.

In January 2022, Chope wrote to the trade department about RCV Engines’ “outstanding export cases which are now causing them dispatch issues”.

He added: “The situation has become urgent”.

Chope also tabled a question in parliament regarding the status of RCV Engines’ licence applications.

An official from the trade department replied to Chope’s letter in February, saying RCV Engines’ licence application was “under active consideration”.

The Export Control Joint Unit, the official added, was “seeking to reach a decision as soon as they can”.

That decision came shortly after, with the trade department agreeing to remove RCV Engines’ engines from its export controls list.

RCV Engines seemed delighted, and credited Chope with the result.

“Christopher first came to RCV in 2022”, the company wrote on its LinkedIn page. “On that occasion he helped us remove the need for an export licence when shipping worldwide. This significantly improved lead times, reduced the admin burden and enabled the securing of more orders worldwide”.

The company added: “The success that we have seen since 2022, which is directly linked to the export control status, has meant RCV has been steadily growing”.

Data on export licensing decisions, obtained via a FOI request to the Foreign Office, suggests RCV Engines has not applied for any export licences since 2021.

But last year, the company seemed concerned by the arms export restrictions on Israel which were implemented by the Labour government, suggesting it was still exporting engines to the country amid the Gaza genocide.

On 3 September 2024, the day after the suspensions were announced in parliament, RCV Engines wrote to the trade department, apparently about the implications for its engines.

The trade department responded two weeks later, attaching confirmation of “goods that we assess as not classified by export control legislation”.

Competitors

The documents raise further concerns about how other drone engine manufacturers in Britain may be exporting to military customers worldwide without licences.

In the correspondence dated 20 January 2022, an RCV Engines employee told the trade department that the company’s “competitors have not been burdened with the licence issues” and can therefore “offer better pricing and lead-times”.

They said the “situation is therefore a huge handicap going forward. Our patented technology means we win business due to better reliability and performance specs however we know we can increase sales if we can match the pricing and delivery dates that our competitors offer”.

The employee listed four competitors that had not been burdened with the licence issue, but the trade department has redacted the names.

It remains unclear whether UAV Engines Limited (UEL), a British subsidiary of Elbit Systems which manufactures drone engines, was listed as one of RCV Engines’ competitors which can ship its goods without a licence.

An analysis by Campaign Against the Arms Trade found that UEL “may have produced UK-made R902(W) Wankel engines used in an Israeli Hermes 450 drone that killed British aid workers in Gaza in April 2024”.

UEL has previously claimed the drone engines it supplies to Israel are exported onwards to a third country.

A spokesperson for the department for business and trade refused to clarify whether UEL Engines or other drone engine suppliers to Israel had received licence exemptions.

They said: “In September last year we took decisive action to suspend certain licences to Israel that might be used to commit or facilitate serious violations of international humanitarian law in Gaza.

“We do not and have not provided individual companies exemptions from export control legislation”.