Forgotten photos expose UK army abuses in Iraq

A shirtless British soldier, clinging to the hair of an Iraqi man whose eyes and nose have been tightly wrapped with black gaffer tape.

A line of eight Iraqi men with sand bags over their heads, crouched in stress positions on a pavement as a soldier points at them from across a street.

These are among several images, published by Declassified today, which further document the abuse Iraqi civilians endured at the hands of British soldiers after the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

They are being published as Iraqis go to the polls in a national parliamentary election where the incumbent prime minister has reiterated calls for Western forces to leave the country.

Some of the photos, taken in Basra in September 2003, show members of the local Garamsche tribe detained by British soldiers from the Queen’s Lancashire Regiment who were ordered to round them up and deal with them “harshly”.

Less than a week later, soldiers from the same regiment would subject Iraqi civilian Baha Mousa and eight other detainees to “gratuitous violence”, including beatings, stress positions and episodes of sexual humiliation, a public inquiry later found.

Mousa, a 26-year-old hotel worker, suffered at least 93 separate injuries and died after an “appalling episode of serious gratuitous violence” by UK soldiers, the 2011 inquiry concluded.

While the details and images from Mousa’s case have been widely covered, the photos of the earlier episode with the Garamsche, and those of detainees being abused weeks earlier have not been previously published by British media outlets.

Declassified could only find the photos on a Russian site with a BBC Russian Service byline and the Germany newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung.

The images were submitted as evidence to the inquiry and were referenced by its chairman Sir William Gage in the hearings and his final report, but have since been sitting in the inquiry’s archived website – until now.

The raid

What happened on 9 September 2003 is laid out in witness statements and testimonies also filed in the inquiry’s archive and referenced in Gage’s report.That day, British soldiers from C Company in the Queen’s Lancashire Regiment carried out a raid in Basra, southern Iraq.The raid’s aim was to punish the Garamsche, who were alleged to be engaging in mafia-like activities in the north of the city including threatening local shopkeepers.

Along with the order which said the company should deal with them “harshly”, one soldier said he overheard a conversation between a major and a captain about the raid.

According to the soldier, the major said he had “carte blanche” to deal with the Garamsche in whatever way he determined. The major and captain denied they used that expression to the inquiry.

The soldiers rounded up a number of men from the tribe and took them to the Old State Building in Basra, and thus began a nightmare ordeal for the detainees.

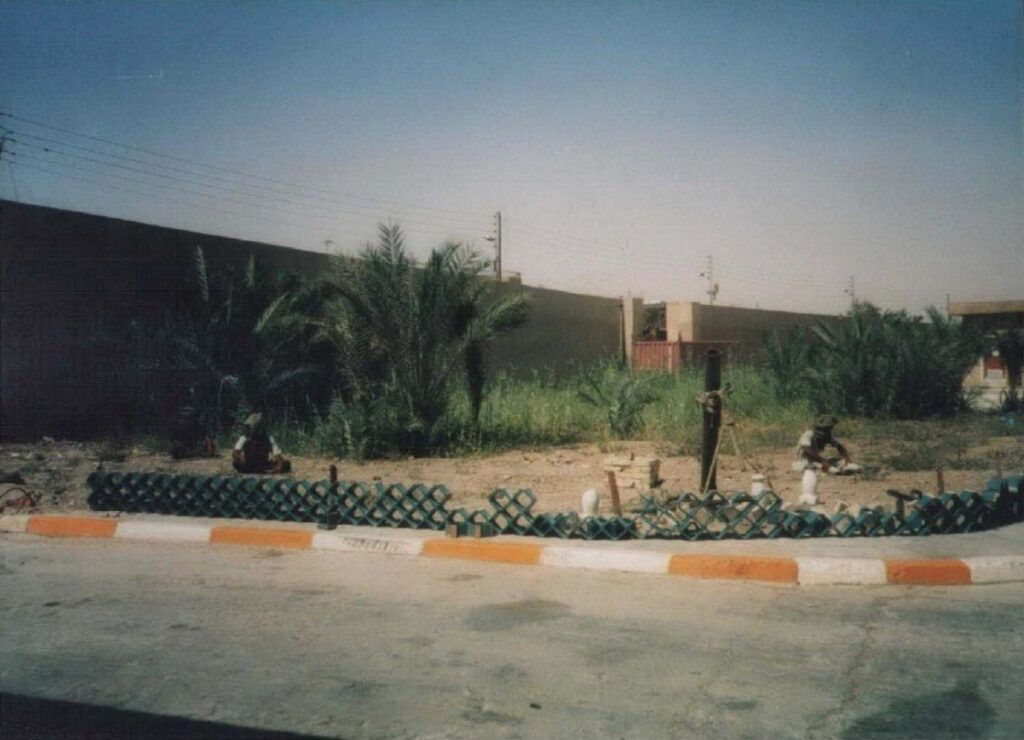

British troops detain Iraqi civilians in 2003 (Photo: Baha Mousa Inquiry)

‘Squealing like pigs’

One soldier testified that the abuse of the Garamsche detainees began even before they arrived at the building, which served as a base for coalition forces.

According to Gage’s report, Corporal James Dunn said he saw four of the detained Garamsche being punched and kicked “whilst being manhandled into transport at the scene of the arrest and throughout the journey”.

“They were screaming and squealing like pigs,” Dunn was quoted as saying.

Lance Corporal Alifereti Nasau, a medic who was not from C Company, also saw detained members being kicked and punched, and noted two men who were bleeding, one from his mouth and an old man with a cut over his eyes.

Private John Morris said he saw a soldier strike a prisoner with a rifle butt.

The inquiry report continues: “On arrest the detained Garamsche were blindfolded for lengthy periods, either with sandbags or by black gaffer tape being wrapped round their heads.

“Photographs graphically show such treatment. In each of these photographs S037 [an unnamed soldier] is shown in distasteful poses crouched by the detainees. There is evidence that he shouted at, punched and kicked these detainees.”

None of the soldiers responsible for the abuse of the Garamsche – some of which is depicted in these photographs – were prosecuted for their part in this episode.

British soldier points at hooded Iraqi detainees in 2003 (Photo: David Brown / Baha Mousa Inquiry)

‘Always hooded’

There are further previously unreported photographs in the inquiry archive that reveal abuse a month before Mousa’s death. They were taken in August 2003 by David Brown, a former sergeant who served in the Queen’s Lancashire Regiment in Iraq.

In a witness statement, Brown detailed how detainees were frequently brought back to the UK’s main base in Basra and abused by British soldiers, including being shouted at and held in a hot, dark building that reeked of bodily waste.

He said detainees were taken there around two to three times each week and “were always hooded with sandbags when they were within the compound and in the open areas”.

Brown said when looking into the internment facility, he would often see detainees sitting on the floor with their hands above their heads and that it seemed their hands were “plasti-cuffed”.

“I would describe this as a stress position because it would not have been a comfortable or normal position that a person would maintain if they had a choice. They would generally be sitting with their backs up against the wall,” he testified.

Brown described the internment facility “as shell of a building” which “smelled of a mix of faeces, urine and sweat”. He said he heard from various people that detainees would sometimes relieve themselves there, but couldn’t remember who told him.

“I recall that there were Portaloos just outside, but I do not know whether these were always fully working. I cannot recall whether there were toilets inside the internment facility,” he said.

Brown took photographs of detainees in stress positions, in sweltering heat, at the base on 15 August 2003. Some were “triple bagged” as punishment for “misbehaving”.

Brown kept a diary and cited an entry from that day in his testimony.

“I wrote ‘23 internees in this morning, all neatly arranged in stress positions with sand bagged heads. Sorry looking bunch. Out all day in sun, some of them, some triple bagged. Poor sods’,” he said.

“I recall being told that some of the detainees had been triple bagged by one of the soldiers guarding them . . . I recall being told that the sandbags were used as a form of discipline, so if the detainee was misbehaving or not following instructions, another bag would be put on, and they would quickly learn to behave.”

He added: “I think I wrote ‘poor sods’ because I remember knowing how hot it was that day, and how uncomfortable it would be for them to be out in the heat like that, but I do not think I ever raised this or discussed this with anyone.”

Again, neither Brown’s testimony, nor the photographs he took led to any prosecutions.

Hooded Iraqi detainees on UK base in Basra in 2003 (Photo: David Brown / Baha Mousa Inquiry)

Unlawful behaviour

Nicholas Mercer, who served as the British Army’s chief legal advisor in Iraq in 2003, has stated that stress positions constitute “violence against the prisoner”, in violation of the Geneva Conventions.

Moreover, Justice George Leggatt ruled in the England and Wales High Court in 2017 that hooding always constitutes unlawful degrading treatment under all circumstances.

The International Criminal Court has stated that when carried out under conditions which impede breathing, hooding necessarily amounts to the war crime of torture/cruel treatment.

Despite the abusive and unlawful nature of these techniques, the UK parliament’s joint committee on human rights noted that hooding and stress positions were both authorised at a senior level within the Queen’s Lancashire Regiment in Iraq.

“We are deeply concerned that it became common ground in this case that the use of hooding and stress positioning of detainees by the Queen’s Lancashire Regiment had been sanctioned by Brigade Headquarters, including by the Legal Officer, Major Clifton.”

One soldier was convicted of inhumane treatment in Mousa’s case, and was sentenced to a year in prison. He was acquitted of manslaughter.

The subsequent inquiry established that many other soldiers had directly perpetrated abuse against Mousa and his co-detainees, and that many more had been aware of the abuse and failed to stop it. None of those soldiers have been prosecuted.